Three Years of Programming Books

Today marks the three year anniversary of the start of my journey as a software developer. I thought it’d be a nice way to kick off the new year by reviewing the most impactful books I’ve read in that time. The world of tech presents a dizzying amount to learn—too much for one lifetime, which makes choosing the right things to focus on essential.

I’m not going to discuss books about any specific programming language. If you’re interested in learning to code and don’t know where to start, The Odin Project and FreeCodeCamp are both excellent websites (and free). Instead this list will focus on books that should be valuable to pretty much all software developers.

Mastering Your Environment

These books are presented first, because I feel mastering your environment is a force multiplier for everything else you do as a programmer. It’s really worth putting in the time to learn your way around the command line, and the ins and outs of Git. It’s also worth really learning how to make the most of your editor, which in my case happens to be Neovim.

The Linux Command Line

This book can’t be recommended enough, particularly if you have little or no prior experience with Linux, or with a UNIX shell. It doesn’t assume any prior knowledge, and by the end of it you’ll feel perfectly comfortable handling day to day tasks in the terminal and writing simple scripts.

Pro Git

This is one of those books I started reading and then immediately found myself relying on at work. You usually don’t need git bisect, but the first time you do it feels like magic. Life-saving magic. Every feature of Git you could ever need is covered here, from the essential to the esoteric, and it also doesn’t skimp on discussing its architecture.

Given how ubiquitous it is in modern software development, I really strongly believe every developer ought to take the time to learn at least a little beyond the basics of git checkout, git add ., git commit, git push and git pull. You’re simply living with unnecessary friction if you have to look up every flag and command, and don’t understand the difference between branching and rebasing.

Practical Vim

Vim (and its more recent fork, Neovim) is an incredibly powerful text editor, but it’s not the easiest piece of software to get to grips with. Practical Vim is unusually structured in that it’s essentially an entire book of “quick tips” about Vim’s many features, rather than a conventional user manual. It’s vaguely broken up into different sections, but can be read in any order.

I learned a lot of tricks for navigating files more effectively, making use of command mode, selecting visual blocks with “ragged” edges, and using Vim’s registers. It definitely made a noticable difference to how productive I am in Vim—maybe one day these gains will offset the time I waste tinkering with its configuration… so whatever your editor of choice is, I highly recommend digging into its documentation and learning more keyboard shortcuts and tricks for accomplishing the most common, recurring tasks.

If you use Emacs, strangely enough I have a recommendation for you too further down the list, despite not using Emacs that much myself.

Software Engineering Principles

These picks are all books that treat what I’d call “best practices” in software engineering. Even if you only code by yourself as a hobby, the second you work on anything bigger than a couple of 50-line files in a single directory, knowing how to refactor effectively and write unit tests will start to become rapidly more important as your projects grow.

The Pragmatic Programmer

This book is a classic, and for good reason. It’s another book of “tips” like Practical Vim, this time focused on principles of working as an engineer. A lot of the advice might feel a little obvious if you’ve already been working in software for more than a couple of years, but I definitely learned a lot as an apprentice from books like this.

Refactoring

Highly, highly recommend this book. Martin Fowler’s a great writer, and his other books and many articles on the web are extremely valuable and worth reading too. I particularly like the care he takes to define words clearly, like the eponymous term “refactoring”, and the engineering objectives they encapsulate.

For example, if you picked up the word “refactoring” from observing its use in context while conversing with other developers, it would be easy to associate it with “rewriting existing code so that it’s more efficient, and/or easier to read”. Fowler quite strongly stresses that refactoring is about making existing code maximally easy to modify, without changing its observable behaviour. In fact this can even be an antagonistic objective to the computational efficiency of the code, but large software projects need to be easily-modifiable to be maintainable, and for teams to be able to continually add new features.

The book is written in JavaScript, and has a fairly strongly Object-Oriented flavour, with some Functional Programming appreciation sprinkled in a couple of places. That said, many of the principles can be exported to almost any programming paradigm.

Unit Testing Principles, Practices, and Patterns

Maybe this is just me, but I’ve long felt many of the introductory unit testing and Test-Driven Development resources online are lackluster, and fail crucially in explaining why testing is important to begin with. Perhaps it’s a topic that’s not normally touched by people who don’t already have enough experience and context as a developer for the value of testing to be self-evident, but I honestly thought after watching a dozen youtube videos of people writing tests for a function that adds two numbers together that testing was about verifying code you’ve just written does what it’s supposed to. It took experience working with other developers (and reading books like Refactoring) to quickly realise that the primary value of tests is in protection against changes to the codebase breaking the behaviour of already-existing code (i.e. “regressions”). This protection allows you to refactor confidently (since refactoring itself is the easiest way to introduce regressions), which allows teams to iterate faster.

This book is absolutely fantastic, and its author, Vladimir Khorikov, shares Martin Fowler’s preference for clearly defining terminology and objectives. He exhaustively covers the purpose of unit testing, the common pitfalls (such as testing implementation details rather than observable behaviour), and stresses that bad tests are actually worse than unwritten tests, as they will produce false positives when refactoring, lowering the team’s trust in the testing system and discouraging refactoring as an activity. He also dedicates much of the book to demonstrating how to write good unit tests, and good integration tests (despite the book’s name, it actually covers integration testing quite deeply), when and how to use mocks, stubs, spies, the difference between them, how to test code which makes database calls, and much more.

In my experience, the pressure to maintain high velocity makes a lot of companies, particularly startups, skimp on testing. It’s understandable, but there’s a long term cost. The principles covered by books like this are so important to the long-term health of software projects—exponentialy more so as they grow in scale, and lines of code.

Computer Science Fundamentals

These books are really books about understanding how computers and code “work” to solve problems. As someone with no formal background in computing, I’ve put a lot of effort into teaching myself as much as I can about computers and computer science. It’s commonly said that computer science and software engineering are very different things. That’s definitely true, but software engineers can also benefit immensely from strong fundamentals in computer science.

Code: The Hidden Language of Computer Hardware and Software

Code is magical. It’s even worth reading if you’ve never written a line of code in your life and just always wanted to know how computers actually work. It builds up incrementally from basic electrical principles to relays and logic gates, all the way up to fully featured microprocessors and the machine code they execute. It’s written in such a way that you can, at each step, sort of imagine how someone could have come up with at least the next step to begin with, and really puts into perspective the astonishing human achievement the computer represents.

Introduction to Algorithms

A standard university textbook on algorithms, commonly called “CLRS” after its authors’ initials. If you can’t make it through, you will at least now own a fantastic doorstop or paperweight.

Honestly, I’m still only about a third of the way through this book, because the mathematical maturity it demanded was enough to eventually make me shelve it until I’d build up some better foundations—funnily enough, I have some friends who had the exact same experience, so it might actually be quite common with books like this. Despite that, even the parts I’ve read so far are enough to make me recommend it without reservation, as it’s an astonishingly good text.

Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs

The one and only wizard book. It’s hard to adequately convey to someone who hasn’t read SICP why they should even read it. You’ll learn Scheme, a dialect of Lisp, which is always fun if you’ve never touched a language in the Lisp family before. But it’s not really about the language: this book teaches you to think about computing in fundamentally new ways. It teaches principles which are universally applicable, as well as providing enough knowledge to start your descent into a dozen different domains like writing interpreters and parallel computing. The problem sets are hard, and more approachable if you’ve got a decent grounding in mathematics, but very stimulating and rewarding to work through.

As a side benefit, learning Scheme made me realise where most of the good bits of JavaScript like foo.map(x => x.bar) originated, and gave me an appreciation for Lisp and Emacs.

An Introduction to Functional Programming through Lambda Calculus

This book pairs great with SICP. I can’t honestly claim I’ve “used” anything I’ve learned from knowing about the lambda calculus, or how to build linked lists, booleans and numbers from thin air with pure lambda abstraction, but I’ll be damned if it didn’t feel edifying learning about them all. Probably more useful for those designing their own programming languages? Either way, this was so satisfying to read that it became an instant personal favourite.

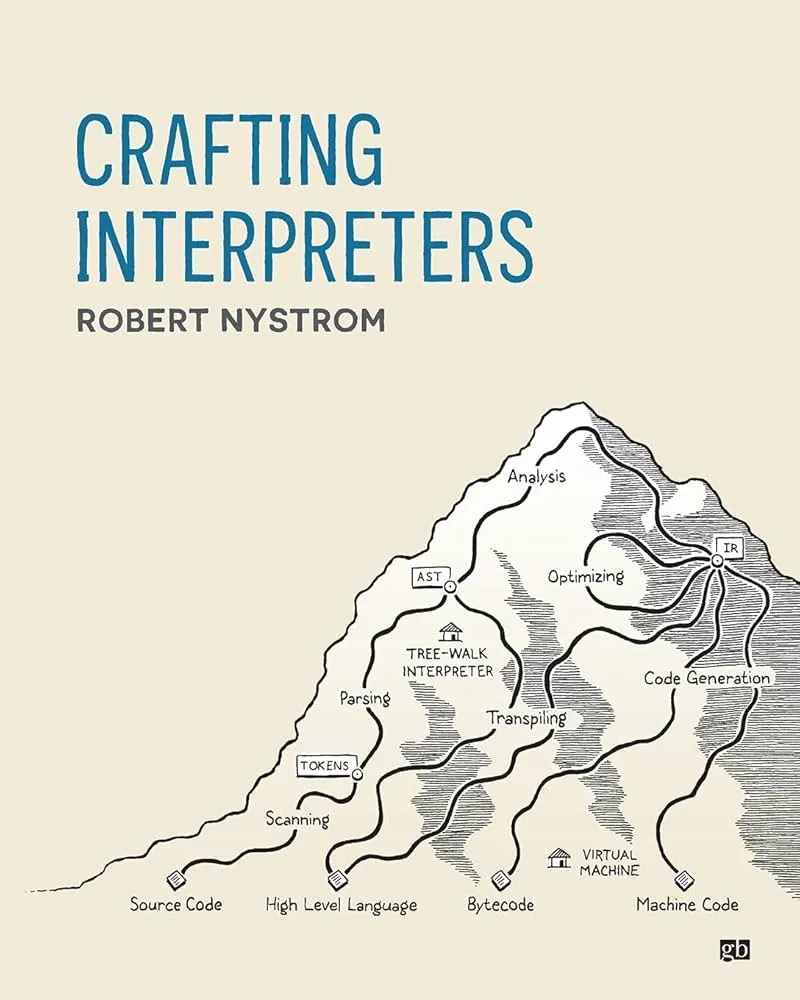

Crafting Interpreters

After reading the above two books, I was left with a real hunger to find something on how to write an interpreter from scratch. Robert Nystrom absolutely delivers. Because he’s a fantastic chap, you can actually read this book for free online, but I encourage you to support him by buying a copy of the book if you can.

For such a heady topic, Crafting Interpreters is actually very easy reading, and there’s zany, hand-drawn illustrations accompanying your journey throughout. If you work through it, you’ll write two interpreters for the same language (“Lox”). The first is a simple tree-walk interpreter written in Java, while the second compiles down to bytecode and is written in C. Even if you’re not specifically interested in building your own programming language, there are a few reasons I think books like this can be valuable as a developer:

- A lot of problems involve parsing information from structured text at some stage. If nothing else, you’ll learn how to write a solid parser by hand.

- A lot of programs eventually want a command console of some kind which begs for a command interpreter of its own to be embedded into the program. A command interpreter is really just an interpreter for a very small language.

- Writing a nontrivial piece of software in C is always worth doing at some point, to gain an appreciation of the concerns your daily language’s dynamic arrays, hash tables and garbage collector handle for you out of view (and their nonzero computational costs).

Wildcards

These books didnt’t really feel like they fit anywhere else, and might appear rather niche. They’re books that surprised me with how much value I feel I got out of reading them.

Hypermedia Systems

A year or two ago there was a brief fad where every tech YouTuber started hyping up htmx as an alternative to the modern JavaScript SPA framework trend. I decided to go straight to the source and read this book, which includes the creator among its authors.

I have to say, I was pleasantly surprised. Not only is htmx pretty cool, but this book is a real goldmine of information about the history of the internet, and the original vision of “hypermedia” and HATEOS (Hypermedia As The Engine Of State). Reading Hypermedia Systems gave me a fresh, and actually older, perspective about a lot of the most taken-for-granted technologies the modern internet rests upon. I’ve built some things with Go + htmx, and it was a pretty enjoyable experience: even if I doubt it will replace tools like Svelte and Astro for me, there are contexts where it can be a perfectly viable tool for the job.

Mastering Emacs

Why am I recommending a book on Emacs? I already told you I live in Neovim. “It’s for Org mode, right?” Nope, I use Obsidian, and probably won’t be switching any time soon. The truth is, I’m not recommending you a book on Emacs. I’m recommending you two books on Emacs.

Okay, okay, hear me out.

I just think it’s a really interesting piece of software, architecturally, and that it actually teaches a lot about good design. I mean think about it, its internals are an eldritch abomination, yet it’s been around since 1976 and is still kicking, still growing, and still represents a non-negligible share of the text editor market. Can you even name another program that’s survived for so long in roughly its original form and still has users?

When you look into its internal structure, I think Emacs is unique in that it focuses first and foremost on extensibility. It’s almost like it takes Martin Fowler’s definition of refactoring—changing code to make software easier to modify without changing existing behaviour—and turns it into a user-facing design philosophy: the application is about as unopinionated about everything as it’s possible to be, instead focusing on providing maximal flexibility and giving users all the tools they need to radically alter the existing functionality at runtime. This is possible because the app is 95% built out of dynamically interpreted Emacs Lisp code, sitting on top of only about a 5% core of primitive functionality written in C.

There are times when you want to build something with impossible to predict requirements. Not just on day 1, but because you want to serve users with fundamentally unpredictable and diverse needs. The Emacs approach is to provide the tools for anyone to meet those needs, not just the core development team. It’s not that dissimilar from the approach of the many game developers embedding a language like Lua into their games and providing tools for fans to create their own mods, or from note-taking software like Obsidian and Logseq being highly moddable, but Emacs is, in my opinion, a particularly convenient software model to study.

This book is essentially a guide to Emacs’ user-facing internals, and how to use it as an application. It’s not too long or burdensome to read, and pairs well with the next book which covers effectively everything else there is to say about Emacs.

The Craft of Text Editing

This book is quite old. It’s older than me, though sadly not by as much as I’d like, and computers have changed quite a bit since it was written. Nevertheless, it covers in immense depth everything that goes into writing a functioning text editor, and in particular how to make an Emacs-flavoured editor built around a Lisp intepreter and command dispatcher.

The original text can be read for free online, and I also highly recommend the following short paper which gives a high level overview of the interaction between the components that make up Emacs.

You’ll learn a lot about the problems, data structures, algorithms and edge cases that go into designing a text editor from reading this book, and I think there’s lessons that are broadly applicable to software engineering to be learned from it. The book uses gap buffers as its primary data structure for text buffers, but exposes them through an interface that allows them to easily be swapped out for others like ropes, which some editors like Zed have been using recently (side note, here’s an interesting discussion on the tradeoffs between a few common data structures for storing text).

I’m planning to write the skeleton of a graphical text editor as my next side project (for reasons that will hopefully become clear soon enough 😉), so this book was of particular interest to me. Your mileage may vary.

Mathematics

A few months into my coding journey, back in mid-2023, I came to a realisation while attempting to read CLRS that my maths chops were rusty, and I’d really benefit from building more solid foundations. Since then, I’ve put pretty much an hour a day into this endeavour and am pleased to say it’s been one of the best decisions I’ve ever made.

Aside from developing skills I’m regularly calling upon at work, studying mathematics has made a world of resources approachable that would have been inscrutable before, and has given me tools to solve problems I had no way of approaching before. As an example, I developed Meantonal as a direct result of studying Linear algebra, and would have never been able to come up with its internals without this knowledge.

This list is just the highlights from the areas I’ve had a chance to read into so far. They’re all elementary books in their respective domains, and great places to start if your maths skills are rusty and in need of attention. It wouldn’t be fair to say that all software development requires good mathematical knowledge, but at the very least it’s something which can come up here and there even in frontend web development. It’s also much easier to study computer science if you’ve also acquired a certain level of mathematical maturity.

Precalculus

The best place to start if you don’t have any existing mathematical foundations. Also a great place to return to if you find yourself struggling with calculus, as most students’ calculus difficulties are actually precalculus difficulties in disguise.

This book’s great in that it’s kind of like a compendium of all the most commonly called-upon areas of maths in day-to-day life. It’s stuff which could come up in almost any technical domain.

Calculus

A classic college text, same author as the above book on precalculus. Not much to say, but it covers everything you’d typically encounter in a computer science undergraduate course.

Introduction to Linear Algebra

This book goes with an online video series and is a fantastic introduction to linear algebra. Being honest, I found LA a much more abstract, less intuitive subject than calculus, and it took quite a while to reach the other end of that tunnel and appreciate its beauty. But it’s also one of the most important areas of maths for the modern world, particularly because of how good computers are at multiplying matrices together.

A Book of Abstract Algebra

This one should be on the shelf of everyone with even a mild interest in maths. It technically doesn’t have any prerequisites, but you’ll benefit substantially from existing study, particularly of precalculus and linear algebra (mostly because LA tends to be most students’ first encounter with noncommutative algebras, and a few of the problem sets involve matrices).

Abstract algebra is honestly one of the more fun areas of maths to me, and I couldn’t put this book down once I picked it up (seriously). It also really opens the door to higher mathematics.

Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications

Discrete maths is a must for computer science, since computers are after all discrete state machines operating on data represented as bits. The book is accordingly very much oriented towards computer science undergraduates, and overlaps a fair amount with CLRS.

Books for the New Year

It’s a new year, and I’ve mulled over my reading backlog a bit and what I’d like to prioritise for 2026. In no particular order, these are the books I want to tackle this year, and why:

Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective

I flicked through the contents of this one, and it seems to hit the spot for covering every level of abstraction in “what goes into a computer, and computer networks” that I’m missing currently. I’d like to read a college text on operating systems at some point too, but this seems like a great “breadth-first search” on computing topics in general, from a programmer’s perspective. We’ll see!

Designing Data-Intensive Applications

Honestly I just see people raving about this book so much online (and in the workplace) that I need to read it and find out once and for all what the fuss is all about. Presumably it’s going to be rather good.

UNIX and Linux System Administration Handbook

I grabbed this one on sale recently. I use Void Linux as my daily driver, and run a little Raspberry Pi home server. I’ve been wanting to dive more into the exact set of topics this book covers for some time, as I’d kind of like to build out my homelab a bit more going forward. Maybe (eventually) figure out how to self-host websites safely.

Deep Learning

There’s no getting away from the advances in AI. I’d like to study it properly, eventually, and this will probably be the first book I tackle on the subject.

The Audio Programming Book

Music was the thing that got me into coding originally, and I’ve always wanted to get into audio programming at some point. This book was a nightmare to find physical copies of and has been on my wishlist for a few years, so when one turned up online recently I immediately jumped on it.

I’m really looking forward to working through this book, and will probably get into DSP programming at some point in the future too.

← Back to blog